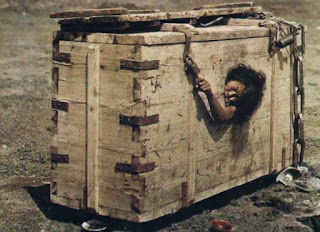

A Mongolian woman reaches out from the porthole of a crate in which she is imprisoned, 1913

A Mongolian woman reaches out from the porthole of a crate in which she is imprisoned, 1913

A Mongolian woman reaches out from the porthole of a crate in which she is imprisoned

July 1913. Note the swastika on the corner next to the lock.

This photo was taken in July 1913 by French photographer Stéphane Passet who was hired by Albert Kahn.

Albert Kahn was a millionaire banker who pioneered color photography using the process invented by the Lumière brothers.

During his trip through exotic countries, Albert Kahn and Stéphane Passet visited Mongolia where they took this picture of a woman who was condemned to slow and painful starvation by being deposited in a remote desert inside a wooden crate that was to become her tomb.

Initially, the bowls on the ground had water in them, though were not intentionally refilled, and the person inside was allowed to beg for food which often just prolonged their suffering as they generally didn’t get enough food for the passersby.

The photographers had to leave her in the box because it would be against a prime directive of anthropologists to intervene in another culture’s law and order system.

The photo was first published in the 1922 issue of National Geographic under the caption “Mongolian prisoner in a box”.

It was the publishers who made the claim that the woman was condemned to die of starvation as a punishment for adultery.

Since then, many people expressed doubts over the story, although the authenticity of the photo is undisputed.

Immurement (from Latin im- “in” and mūrus “wall”; literally “walling in”) is a form of imprisonment, usually for life, in which a person is placed within an enclosed space with no exits. This includes instances where people have been enclosed in extremely tight confinement, such as within a coffin.

When used as a means of execution, the prisoner is simply left to die from starvation or dehydration. Immurement was practiced in Mongolia as recently as the early 20th century.

It is not necessarily clear that all thus immured were meant to die of starvation, though.

In a newspaper report from 1914, it is written: “..the prisons and dungeons of the Far Eastern country contain a number of refined Chinese shut up for life in heavy iron-bound coffins, which do not permit them to sit upright or lie down. These prisoners see daylight for only a few minutes daily when the food is thrown into their coffins through a small hole”.

Comments

Post a Comment